Phishing attacks are growing in number and in technical sophistication. According to the Anti-Phishing Working Group, the number of unique phishing reports it received in 2005 jumped from 7,000 per month in January to over 16,000 per month in December. Furthermore, the impact of these incidents is increasing, with a significant portion in the form of pharming attacks, the newest and most deadly form of phishing. This article summarizes the current threat posed by such attacks and outlines the countermeasures needed to defend against them.

Elements of a Phishing Attack

First, a quick review of the definition of phishing. Simply stated, phishing is a form of Internet fraud in which the criminal tricks an individual into disclosing his or her confidential information so that the criminal may use it for illegal purposes.

Phishing always includes at least one social engineering element and at least one technical element. For example, one well-known phishing attack is the so-called Nigerian scam (named because many of the early attacks originated from Nigeria). The criminal sends an email message appealing to the victim for help to discretely move a large sum of money to the victim’s country. In exchange, the con artist promises the victim a percentage of the money. All the recipient needs to do is provide his or her banking information in order to facilitate the deposit of funds into the victim’s account. Of course, in the end, no funds are deposited, and the victim usually finds that the bank account has been drained. So in the Nigerian scam the phishing attack comprises a technical element (the email message), and a social engineering element (the exploitation of the victim’s greed to gain access to his or her banking information).

Another popular phishing attack involves setting up a phony website that appears identical to the website of a business with which the victim has a relationship, such as a bank. The criminal sends out a spam email to a large number of recipients, knowing that a certain percentage of them will be customers of that brand. The spam email will claim that there has been some sort of security breach and that it is necessary for the victim to click through on a link provided in the email to verify his or her username, password, credit card, pin number, mother’s maiden name, or other personal information. The link, of course, leads to the phony website controlled by the criminal. The phisher then harvests dozens, or hundreds, or thousands of user credentials which can be used to steal money or set up an identity theft. Nearly all large banks, as well as Internet businesses such as eBay and Paypal, have been mimicked in this type of fraud. The technical elements in this type of phishing attack are the email message and the phony website. Social engineering is used to persuade victims that they must take action to verify their personal information.

Over time, the fundamental elements of phishing attacks have not changed; they continue to require both a social element and a technical element. What has changed is the complexity and the number of technical elements utilized to launch and sustain such an attack.

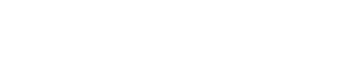

As the technical complexity of phishing attacks increases, so does the technical expertise and energy that security professionals must employ to defend against them. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the growing complexity in phishing attacks and the advanced technical skills required to create them and to defend against them.

In order to fully comprehend the growing threat of phishing it is important to understand how these attacks have evolved over time. In the sections below, we review the growth in the complexity of phishing attacks, their impact, and the controls required to defend against them.

Email Phishing Attacks

The earliest form of phishing attacks lacked both creativity and technical capability. Essentially, they were spam emails that attempted to entice victims to give up their confidential information; once again, engaging a simple technical and crude social element to commit the attack. Not terribly creative, but effective enough to encourage others to improve upon the scam.

As shown in Figure 2, the impact of email phishing scams is mainly felt by individuals rather than businesses. Because these early forms of phishing, such as the Nigerian scam, were often simple and crude, they were easy to spot and the criminal payback was inconsistent.

Controls to combat email phishing attacks, likewise, are simple. Users can be easily trained to spot the signs of email phishing, and anti-spam software can be deployed to catch most of the scam emails before they reach the user.

Brand Targeted Phishing Attacks

As the art of phishing matured, criminals began to target specific companies and their customers in order to improve their returns. These attacks used advanced technical capabilities such as the exploitation of weak website coding or security flaws within desktop operating systems. The phishers combined multiple technical elements along with social engineering to target an attack on specific corporate brands. Phishing attacks reached the big time.

The success of targeted phishing attacks forced companies to take notice, as attacks started to directly impact their businesses. Companies such as eBay and Citibank were witnessing daily attacks on their customers. This strategy of impersonating a known brand produced consistent and lucrative returns for criminals.

As a result, these more sophisticated phishing attacks created new concerns among executives regarding security strategy and corporate liability. Companies could not draw the security line at the edge of the network. Risk mitigation strategies now had to extend to the customer and the customer’s desktop.

To defend against targeted phishing attacks, companies now must assume responsibility for raising customer awareness of the threat. Specifically, companies need to advise customers on the dangers of phishing and the need to maintain a secure desktop computing environment. In addition, they must strengthen the overall technical expertise of their website developers and network engineers to counter the increasing sophistication of phishing attacks. For example,

- Website coding standards must address security concerns. Insecure development practices allow phishers to exploit website vulnerabilities, such a’ cross-site scripting, to redirect unsuspecting users to the bogus website.

- Additional security features can also be designed into the e-commerce site itself, such as Bank of America does with its SiteKey image and text checks, which give customers the assurance that they are viewing the bank’s true website.

- Email systems must incorporate security measures. The SMTP protocol has inherent security vulnerabilities within it that make it easy for an attacker to generate an email that seems like it is from a specific entity. It is a simple matter to forge the “sent from” field in most email programs. With a little more technical savvy on the part of the attacker and some minor configuration alterations on an organization’s email server, an attacker can take it a step further by utilizing the company’s own mail server to actually distribute the message. In this situation, unless the content of the message has clues that it is a fake, it would be difficult for the typical customer to tell that it is not a valid email from the company. Furthermore, SMTP may also be exploited by phishers to send bogus emails to the company’s own internal employees, enticing them to give up confidential information such as usernames and passwords.

Because the threat is constantly evolving, companies must continually monitor trends in phishing attacks, prompting them to anticipate new types of threats and be proactive in building defenses in advance of need. Participation in associations such as the Anti-Phishing Working Group (www.antiphishing.org) can be helpful in this regard.

Pharming–The Attack of the Future

The latest incarnation of phishing attacks is known as pharming. With a pharming attack, the criminal hijacks or otherwise compromises a domain name server (DNS) to redirect web traffic intended for a legitimate website to a different site, often one that is an impersonation of the legitimate site. Phishers can also employ DNS poisoning by compromising an upstream DNS server. Because the compromised domain name leads to the imposter site, no email is needed to lure the recipient. The technical element is so sophisticated that very little social engineering is needed, except to take advantage of the typical user’s lack of suspicion about small differences in the website experience.

Pharming attacks began to escalate in 2005 and are continuing to evolve. These attacks now employ sophisticated technical capabilities, producing security breaches that are virtually transparent to the victim and potentially impact a far larger population. Like the creation of a major motion picture, the time, energy, and resources required for the project are large, but in the end they yield a much larger payout.

The evolution of phishing, like every technology, will eliminate the weak amateur, leaving the competent, sophisticated predator. Pharming attacks, which compromise DNS traffic, are an example of that evolution. Pharming is even more dangerous than common phishing attacks because the differences between the legitimate site and the imposter site are easy to overlook as a fraud, both for the victims and the security professionals attempting to protect against them. Because a large amount of website visitor traffic can be hijacked, the potential damages can be significantly more devastating than phishing attacks that depend on victims responding to a targeted email message. Further, pharming exploits DNS, a complex protocol that involves many valid transactions a day, making it more difficult for organizations to create a logging and monitoring infrastructure that can detect suspicious traffic through this channel.

As shown in Figure 2, the majority of security controls needed to counter the threat of pharming are the same as those needed to protect against brand targeted phishing attacks discussed in the previous section. But organizations must do even more. They should look holistically at critical technologies such as DNS, ensuring that they are designed and maintained securely. To aid in this, they should also provide even more sophisticated technical security training for the senior IT staff that design, configure, and maintain the DNS infrastructure. Large companies often do not take a holistic approach to their DNS design, instead adding and removing pieces in an ad-hoc fashion. Ad-hoc DNS configuration leads to an environment that is technically complex and cumbersome, making the DNS infrastructure more susceptible to tactics such as DNS poisoning and unauthorized zone forwarding. Compounding the problem, companies often have long lists of domain names registered, many of which are not consistent with the brand or identity of the organization. If the organization at times uses these domain names with its client base, it can cause customers to become too trusting of any domain name that claims to be from that organization, even if it is a fake.

As an additional countermeasure, customers should be provided with instruction on methods for detecting website validity. This includes simple items such as teaching users to look for common hints that a site is counterfeit, such as, misspelled words or broken web links, as well as more complex website validation techniques such as reviewing the authenticity of security certificates on the pages that they visit.

The Threat Continues to Grow

Just as con artists have been around for thousands of years, adapting and improving their art, Internet con artists will continue to develop new forms of phishing attacks. Traditionally, these attacks have centered on specific industries such as financial services. However, any organization that does web-based e-commerce is a potential target. The threat is truly a universal problem, and it is imperative for all organizations to review their risk profile and implement risk control measures as outlined in this article to minimize the potential damage. Because phishing attacks employ both technical elements and social elements, countermeasures should include technical defenses as well as user training to make customers aware of the threat.

This article was written by Contributing Research Analysts Ron Collette, CISSP and Mike Gentile, CISSP. They are authors of The CISO Handbook: A Practical Guide to Securing Your Company, published by Auerbach. For more information, please visit www.cisohandbook.com.

For the economic impact of malware, please see our 2006 IT Security Study.