Organizations today must comply with a greater number of regulations than ever before. Because of the pervasiveness of information technology and the ever-changing nature of security threats, many of these regulations deal with the security of electronic systems and the protection of personal information.

This Research Byte is a summary of our full report, Moving Security Beyond Regulatory Compliance.

Although the intent of these regulations is good, their proliferation is burdensome. Organizations often find themselves having to comply with many different but overlapping requirements. For example, regulations such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act apply to a wide variety of firms, while others are industry-specific. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) governs organizations that maintain patient health data, while the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) mandates that financial institutions establish policies for the collection, disclosure, and protection of non-public personal or personally-identifiable information. The U.S. government is not the only regulator. California’s SB 1386 requires any organization doing business in California to protect their customers’ personal information. If companies want to do business in Europe, they must comply with various EU directives. Doing business in Japan, China, Australia, and other markets often involves navigating whole new sets of regulations.

On the positive side, regulatory mandates do compel organizations to address their security requirements where they might not otherwise have done so. From the perspective of the security professional, therefore, the regulations are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they give the security program an important role in the success of the business. On the other hand, the regulations can easily become the center of attention, and the organization can become overly focused on compliance and lose sight of the goal of the regulations–security. It is possible to be compliant but not secure.

Solution #1: Have a Single Comprehensive Security Framework

Because compliance is such an important part of doing business, it is tempting to treat each regulation as a separate “project.” For example, if the organization is seeking to list shares on U.S. markets, it may launch a “Sarbanes-Oxley project” to become compliant with that set of regulations. At the same time, if the organization handles medical records, it may have another program to ensure that its systems are HIPAA-compliant. If it also does government contracting, it might have another project to tighten up procedures to meet those requirements. If next year it decides to do business in Europe, it may launch another project to become compliant with various EU directives. Because compliance is so important to the success of the organization, it is easy to organize the security program around the regulations to ensure nothing is missed.

Although it may appear logical, there is one great flaw in this approach: duplication of effort. Many regulations deal with the same requirements, stated in similar or almost identical terms. Therefore, if the security program is organized around compliance, it may find itself dealing with the same needs over and over again. The security program may become fragmented and overly complex as the organization develops duplicate and overlapping processes to meet what are in fact common requirements.

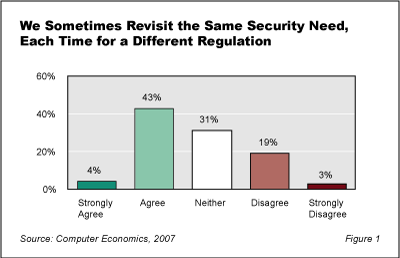

Our survey found that this problem is real. As shown in Figure 1, almost half of our respondents (47%) agree with the statement, “Our security professionals often end up addressing the same security requirement multiple times, each time to meet the needs of a different regulation.” Only 22% disagree.

A better approach is to develop a single comprehensive security framework for the organization, one that encompasses best security policies and practices. If done properly, such a framework will almost certainly satisfy every applicable regulation. A traceability matrix can be developed to show how and where the organization’s security framework satisfies each regulatory requirement and how each regulation is addressed by the framework. This approach allows the security program to manage a single set of policies, procedures, and practices, regardless of the number of regulations it must comply with. It also allows new regulations to be added more quickly, as most if not all of the specific requirements are likely to be already addressed by the framework.

The full version of this report provides statistics to support three additional recommendations for managing security in a regulated environment.

In summary, we find that regulated organizations are best served by a single security framework that can be harmonized with the various regulations, as evidenced by the data above. Second, to maintain the effectiveness of both regulatory audits and security programs, the regulatory audit function should be kept separate and distinct from the function responsible for designing security controls. Third, the security program should go beyond simply responding to audit findings and deal with root problems that result in non-compliance. Finally, the security program should take advantage of regulatory mandates as a justification for prudent investments in new security initiatives.

This Research Byte is a brief overview of our report on this subject, Moving Security Beyond Regulatory Compliance. The full report is available at no charge for Computer Economics clients, or it may be purchased by non-clients directly from our website at https://avasant.com/report/moving-security-beyond-regulatory-compliance-2007/(click for pricing)

Contributing research analysts Ron Collette and Mike Gentile participated in the survey design and analysis of the survey results for this article. They are co-authors of The CISO Handbook: A Practical Guide to Securing Your Company, published by Auerbach.