Nearly all IT projects require some sort of procurement, whether it is for hardware, software, or services. Therefore, IT project managers need to understand the major element of IT procurement contracts, as outlined in this post.

This Research Byte is a summary of our full report, How to Evaluate IT Procurement Contracts.

IT managers make two common mistakes in regards to contracts. First, they often treat contracts as legal matters only and delegate contract review to corporate legal counsel. Although legal review is essential, lawyers often do not have the technical or operational background to evaluate IT contracts from a business perspective. A lawyer may not anticipate what could go wrong in a software implementation, nor might he or she think to recommend a clause specifying, for example, the buyer’s right to request a change in the vendor’s personnel at no charge within an initial time period. Procurement contracts are too important to delegate to the legal department alone. Instead, read through every contract from a business perspective first, and then route the contract through the legal department for final review.

Second, IT managers are often too conservative in their approach to requesting changes to contract language. Vendors of IT products and services generally have their own boilerplate agreements, which they present to buyers as their “standard contract.” Many project managers assume that such contracts are not easily modified. This is a mistake. Such boilerplate language almost always favors the seller, and any contract is an agreement between two parties. The buyer has as much right to suggest language for the agreement as the seller does. Never assume that contract language is cast in stone.

Please note that the information provided in this report is not to be construed as legal advice. Each procurement contract requires legal advice from a competent lawyer to ensure that it is appropriate for the buyer’s situation.

Typical Contract Elements

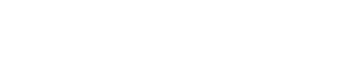

Understanding procurement contracts begins with a knowledge of what such contracts have in common. The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), created in 1951, established eleven articles that all U.S. states (except Louisiana) follow. (Since Louisiana’s legal code is based on civil law and not common law, the state has elected to only follow some of the UCC articles.) All commercial procurements are subject to UCC code–except for government contracts, which fall under the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) rules. Figure 1 shows the major sections that generally exist in all contracts. These sections may not appear in the same sequence in all contracts, or they may appear under different headings than those shown, but they generally appear in most procurement agreements.

Let us review each of these main sections.

-

- The statement of work defines the scope of the agreement. It is a complete description of the work to be done and the requirements to be satisfied under the procurement. It generally appears early in the contract. For example, the contract for a new computer server might include a statement of work that specifies the scope of the contract, including delivery and complete installation of the new equipment.

- Following closely after or combined with the statement of work are item specifications. If the supplier is to build or provide a tangible product, the specification is the definition of the technical requirements for the product being procured. Generally there are three types of specifications found in contracts. First, design specifications describe the problem to be solved or the requirements to be fulfilled by the product. Second, functional specifications describe what the product must do. It is the blueprint for the design of the product from the user’s perspective. Finally, performance specifications provide an understanding of the required level of performance for the product, including specific metrics and tolerances.

- Under UCC Article 2-513, the buyer has the right to inspect the goods prior to making payment. The inspection must be made in a reasonable amount of time to allow the seller to make adjustments if necessary. Therefore, it may be prudent to set up a schedule of specific dates for testing and inspection in the contract, especially if these activities will take place at the seller’s location. Reasonable penalties can be established for failure to comply.

- Whether the vendor is supplying the customer with one item or multiple items, having a delivery schedule in the contract holds the vendor accountable to the customer’s project timeline. The contract can also specify penalties on the seller for failure to meet delivery schedules.

- Warranties can either be expressed or implied. UCC Articles 2-313 and 2-314 discuss each type of warranty. An express warranty, one which is spelled out in the contract, is stronger than an implied warranty, which is generally assumed in procuring products and services of the type under consideration. The warranty section of the contract may also disclaim any warranties express or implied.

- It is important to establish governing law within the contract. If the contract is between two parties within the United States and one party is not a U.S. government agency, then the UCC articles will govern the contract. If the seller’s home base is outside of the U.S., it is prudent to have language in the contract detailing which governing body’s law and regulations will control the contract.

- The order of precedence section sets forth the rank order of procurement documents in the event that there are conflicts in the language of individual documents. For example, in the procurement of a software application, the buyer may generate a request for proposal (RFP), the seller may prepare an RFP response, and the two parties may ultimately agree on a procurement contract. The order of precedence clause of the contract may then specify that the contract terms and conditions override the RFP, and the original RFP overrides the seller’s RFP response.

- The title transfer section lays out the details for when and if title passes from the seller to the buyer for the items that have been procured. For example, a contract for 500 new personal computers might specify that title transfers to the buyer upon completion of testing.

- Companies always have the right to terminate a contract for a “default” in performance, which is a form of breach of contract. To protect the buyer’s interests, it may be wise to have a clause which allows the buyer to terminate a contract for its own convenience. For example, a contract might specify that either party may terminate the contract with 30 days written notice. Or, termination may only be permitted in the event of a serious breach in performance. A termination section should also include what rights and responsibilities are to continue in the event of contract termination, such as the need to protect the trade secrets that may have been disclosed during the course of the relationship.

- Arbitration is usually less costly than litigation but considerably more costly than mediation. If arbitration is will be used to settle disputes, an arbitration clause should be inserted in the contract specifying the intent of all parties, like whether the arbitration will be voluntary or binding.

- Charge-backs are generally costs that the rightful responsibility of the seller–such as to repair defective items–but which by prior agreement will be incurred by the buyer and charged back to the seller. The charge-back section may also include a definition of what charges may not be charged back to the seller.

- The payment schedule defines the terms and conditions for the buyer’s payments to the seller. For example, the payment schedule for a custom-developed system may call for a certain amount to be paid up front, with another amount due upon delivery, and final payment due 30 days after completion of user acceptance testing. There are many ways to pay for goods and services.

The full version of this report provides an overview of the essential elements of IT procurement contracts, the main contract types, and recommendations for choosing the best contract for specific project procurements. It serves as a primer on IT procurement contracts. Our focus is primarily on contracts for IT services, though the principles apply to any type of IT procurement. (An explanation of software licensing agreements, however, is well beyond the scope of this article.) We explain the typical elements of an IT procurement contract and the major types of contracts, including various types of fixed-price and cost-reimbursable agreements. We then provide guidelines for choosing the right type of contract based on characteristics of the procurement or project. We conclude with a checklist that can be used to review proposed contracts.

This Research Byte is a brief overview of our report on this subject, How to Evaluate IT Procurement Contracts. The full report is available at no charge for Avasant Research subscribers, or it may be purchased by non-subscribers directly from our website (click for pricing).