Are Silicon Valley companies such as Hewlett-Packard more prone to dysfunctional boards than other companies? What are the keys for ensuring that a board does not run off the rails?

Are Silicon Valley companies such as Hewlett-Packard more prone to dysfunctional boards than other companies? What are the keys for ensuring that a board does not run off the rails?

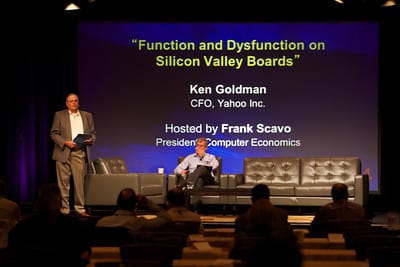

These were some of the questions Ken Goldman, Yahoo’s CFO, addressed in an on-stage interview by Computer Economics President Frank Scavo at the Future in Review conference in Laguna Beach, Calif. As someone who has served on over thirty corporate boards in his career, Goldman had much to say about what works—and what doesn’t—on corporate boards.

How Do You Decide Which Boards to Join?

With his extensive connections in Silicon Valley, Goldman receives many invitations to join corporate boards. But in deciding which to accept, he looks at several factors. First, he looks at who he knows on the board and whether he wants to work with them. As an active investor, he also takes interest in those where he has some “skin in the game.” In addition, he has a strong preference for founder CEOs. “They have a passion that cannot be replaced,” he said. Finally, he considers whether he can add value. With his operational experience and financial background, he can be a logical choice to chair the audit committee.

Goldman pointed to one company that met all these criteria, GoPro, Inc., where he recently joined the board. “I know the people on the board, I like the CEO, and they have a great product,” he said.

When Do You Say Goodbye?

Goldman hates to leave a board when the firm is not doing well. “I don’t like to be seen as a quitter,” he said. As an example, he pointed his recent departure from the board of directors at Infinera, a manufacturer of optical transmission equipment for telecom service providers. “They had some ups and downs in a tough market, but they were doing well in the most recent quarter,” he said. “So it was a good time for me to leave and not be seen as bailing out.”

The easiest time to leave is when there is a merger or acquisition, as investors expect board changes as part of the transaction, he said.

Is a Tech Background Needed to Serve on a Tech Company Board?

With an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering from Cornell, an MBA from Harvard, and his long history in Silicon Valley, Goldman would seem like a natural fit for tech company boards. But is that background and experience always required?

Goldman said tech companies often prefer to have board members with tech experience, but that’s not always the case. Charles Schwab, founder of the financial services firm, was on the board with him at Siebel and now has joined the board at Yahoo. “He may not have a technology background, but he has such recognition and having been a founder CEO himself, his experience is very helpful.” Goldman said.

What Are Some Examples of Well-Functioning Boards?

With his years of experience, Goldman rattled off a list of companies where he has served on well-run boards. For example, there is Starent Networks, where the board comprised some venture capital investors in addition to several independent board members. They went through the IPO process together and ultimately sold the firm to Cisco for about $3 billion.

He then pointed to NXP Semiconductors, where he joined the board just prior to the firm’s IPO and saw the board playing a critical role in bringing in key personnel to grow the business. NXP went public at $14 and is now trading at about $60—a four-fold value creation, he said.

He also mentioned TriNet Group, Inc., a cloud-based professional employer organization (PEO) where the board worked with the CEO to build the executive team in every key function. “You can push and push, but if you don’t have the right team in place, it won’t work,” he said.

At TriNet, the board was able to provide guidance to the CEO in some matters where the CEO was too close to the situation to see things objectively. “The board can add value by seeing the big picture, but not by micro-managing,” he said.

Later, Goldman elaborated on the board’s role: “In tech companies, the fundamental value add is revenue growth, so the board needs to work with the CEO on the business model and strategy. How much do you want to invest in growth versus near-term profitability? The CEO defines the strategy, and the board can help ensure that the strategy makes sense and that the executive team is doing what it needs to do to carry it out.”

Goldman agreed that with many strong personalities, it takes time for a board to learn how to work together. He said directors should spend time to get to know one another outside of formal board meetings. He pointed to his experience at Legato Systems, which was acquired by EMC in 2003. “As we were selling the company, we had a closing celebration in Monterey where we played golf together, and we realized how much we liked each other,” he said. “It would have been helpful if we had had an event like that prior to the closing.”

What are Some Causes of Board Dysfunction?

According the Goldman, the fundamental problem is when board members are not all on the same page. “I can tell when folks don’t have a day job because they pontificate forever,” he said. “They make their board membership part of their ego, instead of having a real job. You need to have board members who have a real respect for what their role is, what it is not, and how to give advice.”

However, board dysfunction is not always the fault of the board. It is up to the CEO and the lead director to not allow a board to become dysfunctional, Goldman said. “It is important for the CEO to know how to work with the board. It is also important to have a board chairman who knows how to work with the CEO, to keep meetings on schedule, and not let them go on and on,” he said.

“It’s good to have a little congeniality,” Goldman said. “It doesn’t mean you can’t have a different perspective or be contrary once in a while. But if you are constantly not seeing eye-to-eye, it’s probably time for you to do something else.”

Goldman said that it is okay to rock the boat as long as you don’t capsize it.

Are Silicon Valley Boards More Prone to Dysfunction?

“Some people like to bad-mouth Silicon Valley boards, and I really disagree with that” he said. “What I have seen on Silicon Valley boards is a tremendous amount of passion. We have skin in the game, we’re investors, and we came to the board because we want to be there.”

Goldman said that there are some differences between Silicon Valley companies and traditional businesses: Board members are often investors and not just part of the CEO’s old boy or old gal network, which is often the case in old-line industrial companies.

He also had nice words to say about venture capitalists, who often play a major role on Silicon Valley boards. “They are involved and engaged,” he said. “So I like to see them stay on the board as long as they can after the company goes public. … They know the history of the company and they understand the vision and the strategy, which are so critical. I like the continuity and their passion and the fact that they have skin in the game. They work really hard and do real work. They don’t just meet to deal with governance issues.”

How Do You Deal with Activist Investors?

Goldman believes activist investors are here to stay, so corporate boards had better be prepared to deal with them. “Their play book is almost always the same,” he said. “They look at what they perceive as excess cash on the balance sheet and giving back capital allocations. So, they push for stock buy backs, spinning off business units, and cost reduction.”

But Goldman said that they add value for their investors and their funds tend to do better than the average hedge fund. As such, he advises board members not to ignore what they have to say. “They tend to be extremely smart. In many cases, including at Yahoo, they come with a good experience base, so I personally like to listen to them.”

He said not all activists are the same. Some activities want to join the board and become insiders, which changes the dynamics tremendously. In other cases, they want to stay on the outside and push for change. Some activists are more operating focused, some are just focused on the financials. “Others just want to get the company to do certain things … and in many cases their suggestions have been productive for the company,” he said.

What’s the Story with HP’s Board?

During audience questions, FiRe’s conference chair, Mark Anderson, asked Goldman to comment on the situation with HP, which many consider to be the epitome of a Silicon Valley company with a dysfunctional board. Goldman traced the start of HP difficulties to the hiring of Leo Apotheker as CEO and HP’s acquisition of Autonomy. “I watched HP during the Autonomy acquisition,” he said. “I blasted some of the advisers they had, and I asked, ‘How can you acquire a company for 25% of your market cap with cash that you don’t have when it’s only going to add one or two percent to your revenue?’”

Goldman said you can you blame Autonomy for being a bad company, but you can also question whether HP should have acquired Autonomy in first place. “It’s not easy to bring in a real outsider from Europe as CEO into a Silicon Valley company, into an iconic company like HP that is so proud with such culture and such DNA, and make that work,” Goldman said. “HP has gone through a number of transformations over time, so ensuring that you have the right CEO and the right board is so important.”

He added, “People like to blame the accounting, or the company being acquired, but sometimes the board just has to look in the mirror.”

Register for FiRe2015

Ken Goldman was one of many speakers this year at the Future in Review conference, which focuses on the future of computing and communications, economics, education, energy, the environment, global initiatives, healthcare, and pure science. Other speakers included Vint Cerf, Michael Dell, John Hagel III, Mark Hurd, Peter Lee, Barry Briggs, and David Brin, among others. The complete list of speakers is on the FiRe website. Next year’s conference will move to Stein Eriksen Lodge, in Park City, Utah. Registration is now open on the FiRe website.